“Wise men forever have known that a nation lives on what its body

assimilates, as well as on what its mind acquires as knowledge.” MFK Fisher

One of my favorite December dinner parties takes place on the pages of the short story, “Babette’s Feast.” The year is 1885 (or so). Madame Babette Hersant, a French refugee from Paris, has lost her husband and her son to civil war and, for many years beyond, has been living in exile and working as a servant in Norway. She is, nevertheless, indomitable and when good fortune tracks her down, she resolves to bring transcendent joys to the devout sect of fussy eaters who took her in.

Whenever I indulge myself in the story of this feast, I travel to Berlevaag Fjord, Norway. It’s a snowy evening in the remote Norwegian village no matter what time of year I read the story, but it’s never bitter cold. As I advance toward the pages of the grand feast, I know twelve guests will arrive wearing black frocks with gold crosses. They will dine “in a low room, with bare floors and scanty furnishings” scented with smoldering juniper twigs. And, they will be resolute about one thing—-silence—-upon all matters of food and drink. Because although the villagers have agreed to a celebratory feast orchestrated and prepared by the refugee who has lived as a devoted, peaceful servant amongst them for many years, they have also allowed rumors about strange foods being delivered from odd places in the world for this very feast, to sway their sensibilities—-foods so unfamiliar, they must surely be harmful. Serpents. Turtles. Frogs. Snails. These kinds of foods, the devout sect at Berlevaag Fjord believes, could only be consumed by those who live one snowflake away from complete immoral seduction by “the flames of this world.”

On the December Sunday of Babette’s feast, a last-minute guest—-a traveler in low spirits—-arrives. This guest doesn’t know what he’s in for and as soon as his taste buds make contact with Babette’s first course—-and his first glass of wine—-his senses go berserk. This is when the party really gets going. The mysterious foods and wines are outed by the last-minute guest as the legendary dishes and drink pairings of “a person once known all over Paris as the greatest culinary genius of the age, and—-most surprisingly—-a woman!” Dinner conversations around the table simmer before rising to merry levels of humorous entertainment. Eventually, every guest surrenders to a festive holiday buzz and the reader (she has, by now, fetched her own goblet of good cheer) imagines herself far, far away having a wonderful time while sharing food with foreigners.

Babette’s feast goes on to reach a savory climax before boiling over with despair and heartbreak. I won’t give away what saves Babette, but I will say that her pious benefactors can hardly unwrap the complexity of their emotions. They comfort themselves with faith in a redemptive heaven filled with angels and second chances.

There’s a movie version of Babette’s Feast and it’s delicious entertainment. But the short story written by a writer I cherish—-the inimitable Isak Dinesen—-is best of all.

Like the unexpected guest at Babette’s feast, I often set out on my travels through the frightfully stormy year of 2017 in low spirits. I went in search of comfort feasts and dinner guests that wouldn’t knock me into monotonous stupors of gloom and doom. I was hungry. Hungry in the way MFK Fisher describes hunger in her book, The Gastronomical Me:

“….like most other humans, I am hungry. But there is more to it than that…We must eat. If, in the face of that dread fact, we can find other nourishment, and tolerance and compassion, we’ll be no less full of human dignity.”

And so, my husband and I took our children with us to taste Oaxaca (wah-HA-ka), Mexico. The choice to travel deep into the heart of Mexico was a deliberate one. I was on a mission to see Mexico from a new perspective and to rescue my family from the bombast of America’s president and his political supporters who blabbered on about Mexicans as “bad hombres.”

We found ourselves feeling woefully foreign and isolated in a place on the planet protected by four rugged mountain ranges. It was January. An earthquake shook our eyelids apart the first morning. Then it was mezcal, tasted all day long on a fascinating tour through the humble, artisanal outposts of authentic producers, which purified our tastebuds and bellies for more adventures to come. In Oaxaca, the languages, arts, customs, and cuisines of indigenous peoples have endured history’s continuous cycles of conquest, xenophobia, and modernization. We couldn’t speak the languages we heard in the vibrant markets nor could we seem to fully understand and translate the unfamiliar processes for creating the region’s cuisine within our own kitchen. Yet never have such cacophonous markets paired with a complicated cooking class felt so enchanting.

Perhaps it was the chili peppers. We learned from Nora Valencia, our cooking teacher, that the capsaicin in chilies guarantees fiery games of chance to everyone no matter where you come from. It’s not always possible to know how hot a pepper can be, so choosing to partake in their mysteries is like jumping into the heat of reckless love. Capsaicin in chilies is a stimulant and an analgesic with a reputation for triggering endorphins which means, of course, strange pleasures await. And, as with many peculiar amusements taken by mouth, chilies can be addicting.

Perhaps, on the other hand, it might have been the markets. At the Tlacolula Sunday Market outside of Oaxaca City there were women dressed in traditional Zapotec garb (still authentic) pouring selections of locally sourced chapulines into our hands, gratis. You know what I’m talking about. Roasted grasshoppers. The bugs might have been flavored with garlic, lime juice, salt infused with the extract of agave worms, or plain chile. We remembered we were foreigners and graciously accepted the offerings. But then what? Throw them away? (So rude!) Store them in our pockets for later? Eat them? We smiled then followed our noses to the distractions of an exciting setup for brave foodies—-long rows of sturdy, communal barbecue grills, aflame and smoking up a storm inside a roofed market. The grills were flanked by market stalls strung with cuts of meat from all parts of (within and without) cows, goats, and pigs. I think. But I still don’t know for sure because we had never seen so much meat displayed, in so many unfamiliar ways, without refrigeration. We bought some of the meats using the point-and-hope method of selection. Copying the locals, we bought vegetables too. Then, it was time to cook our feast. We chose a random grill.

Right away, our onions slipped through the grate and onto the hot coals. A handsome Zapotec family strolling through the market stopped to share guidance. The children were dressed in crispy white Sunday clothes and everyone’s face sparkled with good spirits. All communication happened via smiles back and forth through veils of foodie-fragrant smoke. I couldn’t believe it, but another Zapotec man—-with his bare hands—-lifted our barbecue grate to rescue the onions from the coals, which must have been glowing since pre-Columbian times. When no one was looking, I touched the grate to see if it was hot. (Ay caramba!)

For our final meal in Oaxaca City (after several days tasting the best mojitos in the world at the Pacific Oaxacan coastal outpost of Mazunte) we chose to dine at Casa Oaxaca. The exotic, flavorful, foodie performance art of this fine restaurant in a foreign land made our senses go berserk. So consumed by the “flames of this world” did we become, that after our once-fussy eater Wyatt ordered, to start: Tostada de gusanos de maguey, chapulines, mayonesa de chicatanas, aguacate, cebolla, rábanos (Fried tostada with agave worms, grasshoppers, chicatanas ants, guacomole, onion, radish, and mayonnaise infused with chicatanas ants), and after our server created a fiery salsa before our eyes, and after our meals arrived drenched in the storied moles (moh-LAYS) of the region, we requested, in the end, every single dessert on the menu and passed them around without a note of silence. Our expressions of pleasure and joy joined in with the music of the evening’s outstanding trio of musicians and the sounds of a timeless city in the dark of night. I dream of our rooftop table now. A place of peace, comfort, and exciting adventure.

By the time we returned to America, we would know new truths about the foods that fuel our passions and how other peoples of the world need them as much as we do. The state of Oaxaca, we discovered, is and always has been, one of the world’s greatest culinary epicenters. Indeed, every holiday feast prepared in America owes the abundance of its variety and traditions to so much of the genius culinary heritages of Mexico. For instance, the tomato came from Mesoamerica. (Not Italy.) Maybe you already knew that. But did you know it was Mexican chefs, preparing their own grand banquets a long, long, long time ago, who bravely introduced the tomato into the cooking pot? When Europeans first encountered the tomato, they feared it. To them, a fruit so bright and beautiful…colored red…taken by mouth and swallowed so close to the soul…could only lead to misfortune “in the flames of this world.” Ah, the tomato. Fake classified and declared by the US Supreme Court in 1893 (for purposes of 1887 tariff laws) to be a vegetable—-even though science-based botanical knowledge classifies the true existence of tomatoes as one of Earth’s most desirable fruits. A berry no less!

We know our travels aren’t suited for everyone. In Oaxaca, we stayed in an inn where the doors were never locked. We consumed a bottle of Pepto-Bismol too, but also learned that it isn’t just foreigners who are sensitive to unsafe water because no one “builds up a resistance” to bad water, not even the people of third world countries.

Nevertheless, after returning home we were inspired to prepare and present some of our tastiest works of art to be shared in our own extraordinary settings. In these ways, we became most of all like Babette—honoring our greatest artistic selves while enjoying, as Babette says, “something of which other people know nothing.”

********************

Eric and Theresa’s On-The-Road Crab Cakes

1 1/2 cups Maine Rock Crab

1/2 cup crushed Trader Joe’s oyster crackers (about 1 cup before crushed)

Just enough mayo to moisten (about 1 heaping tablespoon)

Squeeze of 1/2 lemon

Thyme

Salt and Pepper

(If you have it, you can add an egg, beaten. We didn’t have any eggs.)

Canadian Dulse (Seaweed/algae) fried in olive oil.

Arugula

Your own favorite remoulade, boosted with smoked and dangerous hot chili peppers from Oaxaca.

Shape the crab mixture into four, lofty cakes about 1” thick. Cook in olive oil, 4 minutes a side creating

a nice crust on each side. Arrange on a bed of arugula, surrounded by fried dulse, with remoulade.

Serve accompanied by a mezcal cocktail upon an extraordinary picnic table.

Markets and Cuisines of Oaxaca, Mexico—A Valley in the Sky at 5,102′ Deep in the Heart of Mexico. Cooking Class with Nora Valencia in Oaxaca City.

Nora Valencia, our cooking teacher. We toured the market near her home before learning how to cook!

At Nora’s home, I saw this on the wall—we weren’t aware she’d been featured in National Geographic Magazine. Good luck for us! Did her cooking class in Oaxaca City change our lives? Yes. In so many ways.

Like the cooking classes we have taken in Rome, Florence, and Paris, the kitchens of foreign chefs are often so small and yet the flavors and meals that are created in them are so big and wonderful!

Nora sculpts a blessing onto the tamale pot.

Nora gave us tongs for the delicate work of roasting peppers and vegetables just right. She,though, is able to use her hands to deal with the heat!

The Sunday Tlacolula Market

Taking our chances and buying peppers from random vendors.

The point-and-hope method of meat selection.

A beautiful Zapotec family stops to guide us in the market.

We ate our grilled lunch in the Zocalo near the market, then tried to find our way back to Oaxaca City. We ate two chocolate cupcakes, too.

Fine Dining at Casa Oaxaca

Tostada de gusanos de maguey, chapulines, mayonesa de chicatanas, aguacate, cebolla, rábanos (Fried tostada with agave worms, grasshoppers, chicatanas ants, guacamole, onion radish, and mayonnaise infused with chicatanas ants.)

We ordered every dessert on the menu.

Scenes of Oaxaca City and Monte Alban

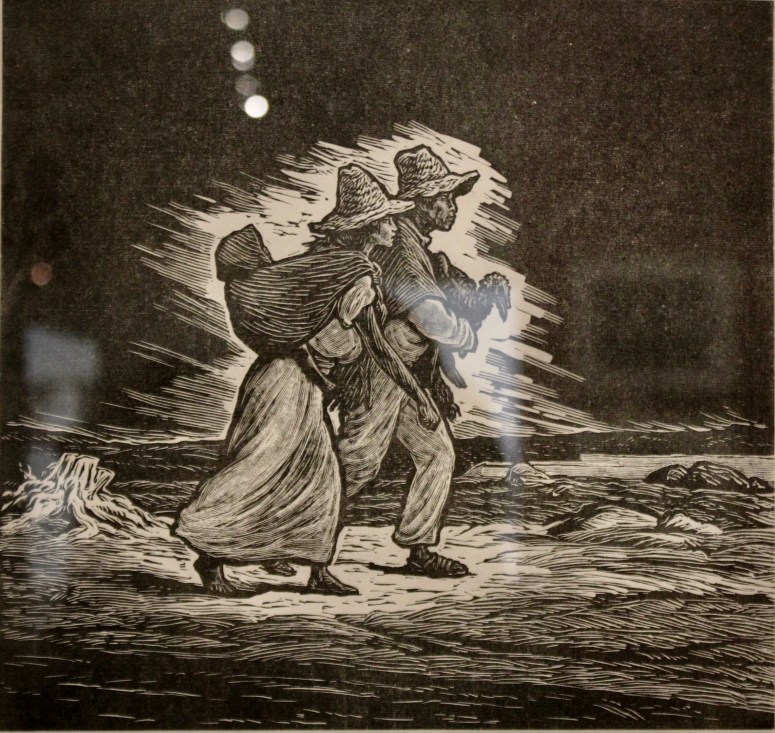

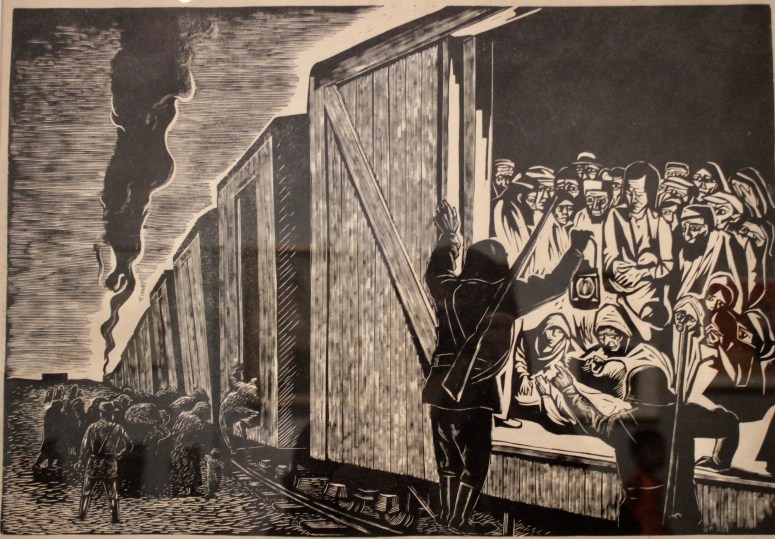

Long line at the art museum.

Monte Alban—one of the earliest Mesoamerican cities and Zapotec center of political, economical, and cultural existence for 1,000 years. Pre-Columbian. Only partially excavated (80% of the site still hides from the modern world). The city which dates from at least 500BC was built on a mountaintop at 6,400′ which had been flattened. Zapotec Sacred Mountain of Life.

Resin of the Copal Tree used for incense in Mexican Churches. Used by the Mayans and Aztecs for ritual supplications and ancestral guidance.

As we departed, a dust devil whirled up around us. Our guide told us it was a great sign—that the power of Monte Alban was removing evil spirits from our family.

Our guide admired our son’s journal sketches, then recommended we try escamoles sautéed in butter and cilantro for lunch at a local restaurant. Ant larvae.

Mezcal by Artisanal Producers

Private Guide Alvin Starkman’s Outstanding Educational Tours

The pits where agave is roasted and from whence the rich, smoky flavors of mezcal are born.

Scorpions in some bottles of mezcal.

Artisanal Chocolate Making and Weaving

Stone grinding chocolate for hand-whipped hot chocolate. Note the abundant beauty of the family’s shrine. While sipping hot chocolate with them, we learned a lot about how one family continues to thrive, while living and working together, through the generations. Hint: Not only is it difficult to live with extended family members and their children, but even the family dogs can wreak havoc on relationships!

Crushed cochineal (scale insects on cactus) revealing the coveted red dye they produce. This little insect, native to Oaxaca, created a sensation that rocked Europe for three centuries and threatened to destroy the cultures of Mexico completely. Read all about it. A Perfect Red: Empire, Espionage, and the Quest for the Color of Desire.

An escape over the mountains to Mazunte on the Oaxacan coast in a small plane. (Aerotoucan Airlines—no flight attendants, no locked pilots cabin.) We stayed at Casa Pan de Miel. A heavenly hideaway on the rugged Pacific Coast.

Balcony porch of our room.

Night walk on the beach and—yes—some pizza! Barefoot dinners.

More than 100 steps from our inn down the cliffside, through the gate, past all the iguanas and on to an expansive beach for long walks through pounding surf.

Mazunte is a center for sea turtle preservation.

Street festivals and street food in Mazunte and a lot of barefootin’.

Walk the beach and stop to drink and/or eat in cafes dug into the sand.

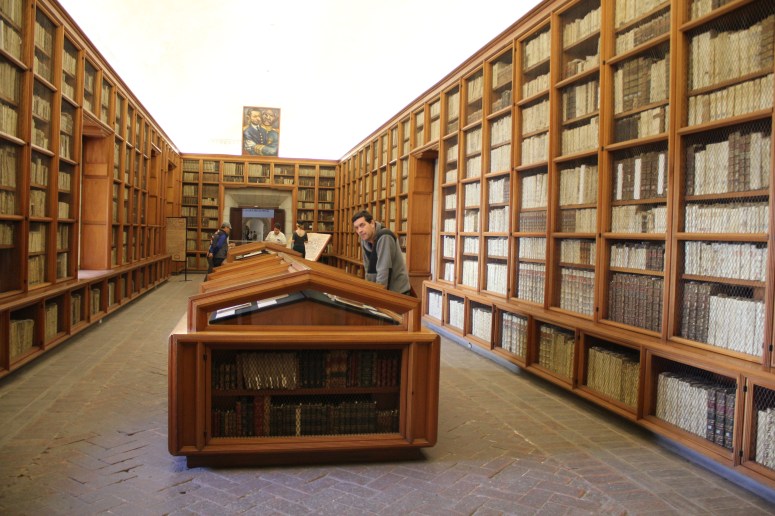

Our digs in Oaxaca City. Casa Colonial. With a library that made it tough to ever leave the gardens and grounds.